This article is about the Virtual Gullah Geechee Program Series by Brookgreen Gardens that was held on Wednesdays from February 3 to May 19th, 2021.

Written by Betty Ogburn

If you’re anything like me (a 90’s baby), chances are that you spent a lot of your early childhood watching the Nick Jr. programming block on Nickelodeon. While there was a plethora of classic T.V. viewing that came from that block (Franklin, Blue’s Clues, Little Bear…), without a doubt, the show that had the most immaculate vibes was Gullah Gullah Island. With its colorful sets, musical interludes, and a lovable polliwog called Binyah Binyah, the series was both fun and refreshing, especially considering its positive representation of a close, stable, and functional African-American family.

While the show’s eponymous island may be fictional, the Gullah people of the title are very real and very much alive today. For those not in the know, the Gullah (also known as Geechee) are a group of African-Americans in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida who descend from enslaved Africans from the “Rice Coast”, which includes modern-day Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. While the exact origins of the terms “Gullah” are unknown, it may derive from “Angola”, which is where the ancestors of many of the Gullah are believed to have come from. Likewise, while the exact meaning of “Geechee” is also uncertain, it may come from the name of the Kissi people from West Africa.

The other day, I had the pleasure and privilege to learn more about this often-overlooked group of Black Americans with a seminar hosted by Brookgreen Gardens. Led by Mr. Ron Daise, who (fun fact!) portrayed the father on Gullah Gullah Island, the seminar delved into two aspects of the musicology of the Gullah Geechee people: pitch and rhythm.

As is the case with all African-American dialects, the distinct pitch of the Geechee has its roots in the sounds of their enslaved African ancestors, particularly the “spirituals” they sang. Also known as “sorrow songs”, spirituals are a genre of music that is, as the name implies, religiously-themed. Oftentimes, the performers would relate their conditions under slavery to biblical characters who received freedom through faith in God, expressing hope for an everlasting peace and rest. These sorrow songs take numerous stylistic elements from folk music found throughout West Africa, including a prominent use of the pentatonic scale, call-and-response structure, and the polyrhythmic, percussive beating of drums. Slave masters feared that such music revealed pagan idolatry, and thus often banned its performance. Nevertheless, enslaved Africans continued to perform their music in secret, holding “community sing” events that still take place in the Gullah community to this day.

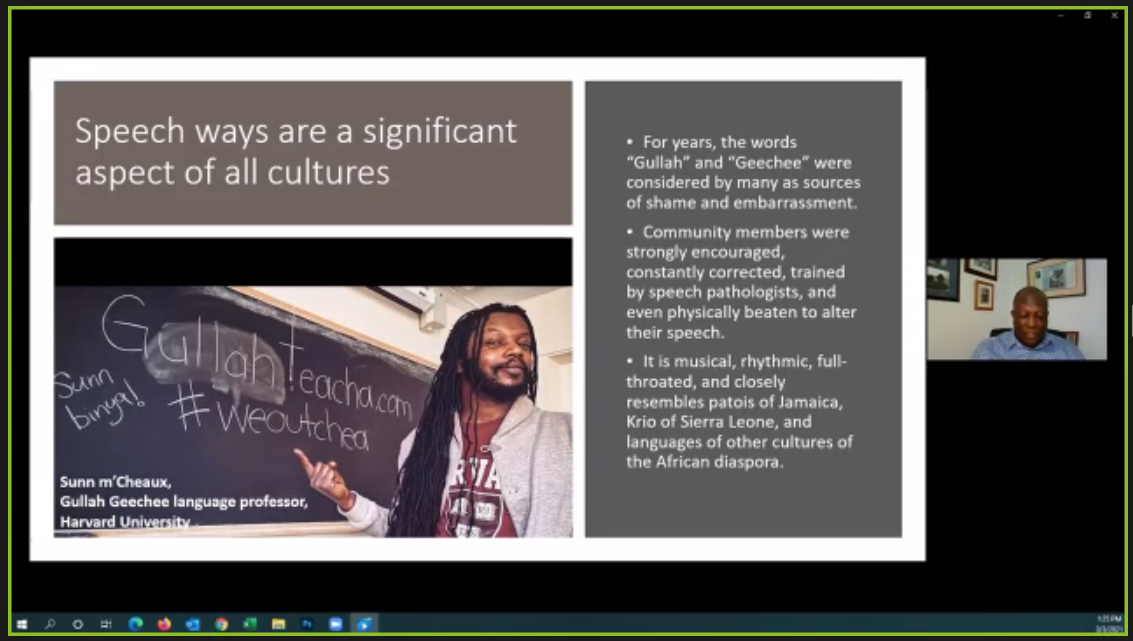

It’s an unfortunate fact that, for many years, the Geechee dialect was often viewed as low-class and illegitimate. In truth, however, it’s anything but! Its rhythm and musicality are similar to those of Jamaican patois, Krio of Sierra Leone, and many other languages found throughout the African diaspora, taking different linguistic elements from various countries. Furthermore, while there is no official orthography for Gullah, owing to its having been only an oral language for centuries, various attempts have been made to transcribe the language. Indeed, there’s even been a translation of The Bible into the Geechee tongue, called The Nyew Testament!

Sadly, my time spent with Mr. Daise was far too short: I felt as though he had barely scratched the surface with sharing his fascinating heritage. Thankfully, there is more to come, because Part Two of this “Musicology” series will be held in the spring and summer months! If you’re like me, and you want to discover even more about the Geechee, be on the lookout for registration information to appear on the Brookgreen Gardens website soon!